Blues & the Commemorative Landscape Project

[Annise Bradley, DeWayne Moore, Shannon Evans, and Kechia Patton Brown]

August 3, 2021

In July 2021, Monument Labs announced Re:Generation - an open call seeking 10 collaborative teams rooted within a neighborhood, city, or region working on a locally-grounded, grassroots art and justice project. Re:Generation seeks applications from teams of two or more individuals working together, proposing a new or expanding upon an existing public-facing art, research, commemoration, and social justice project.

Each team will receive a total of $100,000 toward their local commemorative campaign or project to collaborate across Re:Generation sites and in coordination with Monument Labs on a broader campaign of public engagement and participatory data collection in Spring/Summer 2022.

Monument Labs hopes to fund projects with the power to complicate local and regional narratives, particularly in commemorative ecosystems primed for interventions that bring about a more transformative future.

The core criteria, conditions, and preferences of the search committee at Monument Labs for Re:Generation align almost perfectly with the mission and work of the Mt. Zion Memorial Fund, a Mississippi non-profit that promotes the inclusive and responsible practice of memorialization, historic preservation, and public humanities in Blues communities.

We serve as a conduit to provide financial and technical support to African American churches and cemeteries, and we collaborate with the descendants of Blues artists and Blues communities to research, design, and install memorials that transform abandoned cultural resources into international tourist destinations.

Our work is not another hollow gesture to “keep the blues alive."

The music is very important, to be sure, as a uniquely African American art form that rose about in the 1890s, when racial stereotypes, disfranchisement, segregation, and extra-legal violence coalesced into Jim Crow.

But the music is only the soundtrack--that primal scream connecting the long history of struggle from the past to the present. We work with descendant communities to prevent the erasure of cultural heritage in Blues communities by any means necessary--whether it’s erecting 25 memorials for blues artists, supporting legal remedies for desecration and land dispossession, or publishing research in various print and digital mediums.

"Our work is about more than the blues. It’s about saving the soul of Mississippi."

—Raymond "Skip" Henderson, Founder of the Mt. Zion Memorial Fund

Our work builds on the growing interest in the inclusive process of memorialization and the role memorials play in the process of racial reconciliation. From the framework that regards memorials as instruments of reparations that keep the past visible, we seek to raise historical consciousness about the lived experiences of African Americans and re-orient the goals of blues tourism through the curative processes of memorialization, investigation, and maintenance.

By devising new art and history installations at historic African American sites, developing a blues-in-schools curriculum that situates the music in context with African American history, and creating a digital Atlas and archive that incorporates oral histories, community-engaged research, and immersive online exhibitions, we strive to invest as many stakeholders as possible in each project and help Blues communities reach a consensus about the past—the crucial first step in any serious effort at racial reconciliation.

Our Janus-faced intervention into the commemorative landscape stands in bold contrast to Lost Cause mythology and monuments, complicating the sanitized, state-sponsored historical narratives on the heritage trails and promising a more self-conscious and transformative future.

The commemorative ecosystem in Mississippi

is primed for a meaningful intervention.

In 1949, Mississippi Department of Archives & History (MDAH) director and longtime leader of the Sons of Confederate Veterans William McCain inaugurated the historic marker program to "encourage justifiable pride" in the southern way of life and "stimulate tourist trade" in "the closed society," as historian James Silver referred to the Magnolia State, which defined race relations along a rigid color line. The publication of Silver's book coincided with the passage of the 1964 Civil Rights Act, which signaled the decline of dejure (legal) forms of racial segregation.

But the state's historic markers remain on display, and the southern way of life persists in more polite displays, insidious initiatives of passive aggression.

In 2003, a predominantly African American delegation revived the marker concept during the term of Democratic Governor Ronnie Musgrove, but the original purpose of the Blues Commission was to redress the legacy of racial segregation. The Mississippi Blues Trail originally promised to 1) redress economic inequality, 2) improve the state’s image as an intransigent racist backwater, 3) encourage historic preservation in African American communities, and 4) promote racial reconciliation by telling uncomfortable truths about the state's dark racial past.

Musgrove, however, lost the election to Republican Haley Barbour the following year, and most members of the original delegation “were pushed back…and other people came in and took control,” abandoning its racial justice imperatives. In the end, the Blues Commission awarded millions in lucrative no-bid contracts to a white-owned graphic design and advertising firm [Hammons & Associates of Greenwood] and hired an all-white creative team of music enthusiasts with no academic training in African American history or connections to descendant communities. By carefully controlling the design, fabrication, content, and economic incentives of the Blues trail, the Blues Commission promoted racial division--not reconciliation--through an exclusive process of commemoration, a strategic campaign of economic development in predominantly white business districts, and an passive aggressive pogram of erasure in the Blues communities in Mississippi.

In late 2019, Mississippi state auditor Shad White recommended that the Mississippi Legislature abolish the Blues Commission, because he discovered that it “failed to retain documentation for over $964,000 in payments to vendors and paid $1.9 million to vendors without a contract.” While the Office of the State Auditor and the onset of the Covid-19 pandemic combined to stall its productivity, the Blues Commission remains a powerful force that shapes public memory in 2021.

The Mississippi Freedom Trail

Much like the curriculum on civil rights history that legislators in the 2000s made mandatory in Mississippi high schools, the historic markers on the Civil Rights trail assert self-congratulatory and enlightened bona fides that place inspirational stories of overcoming racial inequality squarely in the nation's past, obscuring any connection to contemporary injustice. The iconization of the movement on the Mississippi Freedom Trail seems to politely suggest that Americans, specifically people of color today, lack the same grit and virtues of these civil rights heroes and heroines.

At a time when new movements for racial and economic justice have emerged on the national scene, this fable of a movement became a potent obstacle and bludgeon used to diminish contemporary efforts, making today's activists seem inappropriate trouble-makers who lacked the gravitas of yesterday's activists and who just weren't going about it the right way.

—Jeanne Theoharis, A More Beautiful and Terrible History: The Uses and Misuses of Civil Rights History (Beacon Press, 2017), p.2.

Blues & the Commemorative Landscape Project

[Annise Bradley, DeWayne Moore, Shannon Evans, and Kechia Patton Brown]

August 3, 2021

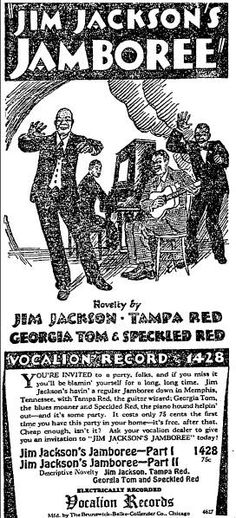

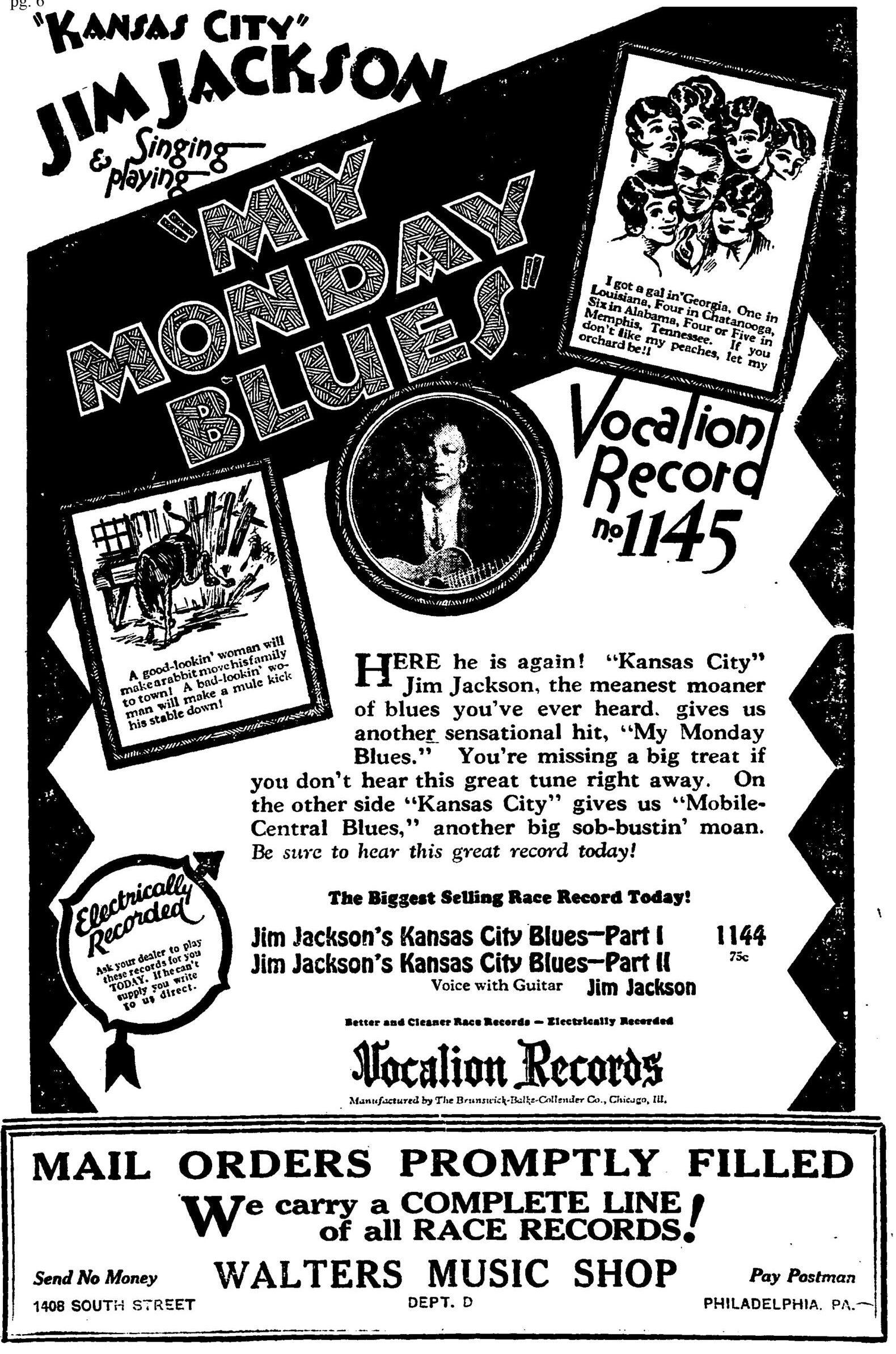

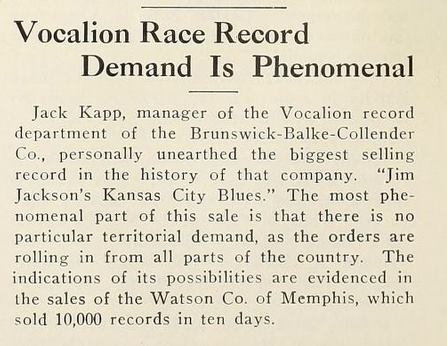

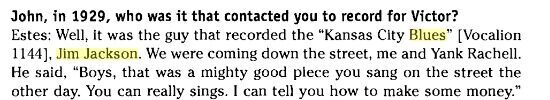

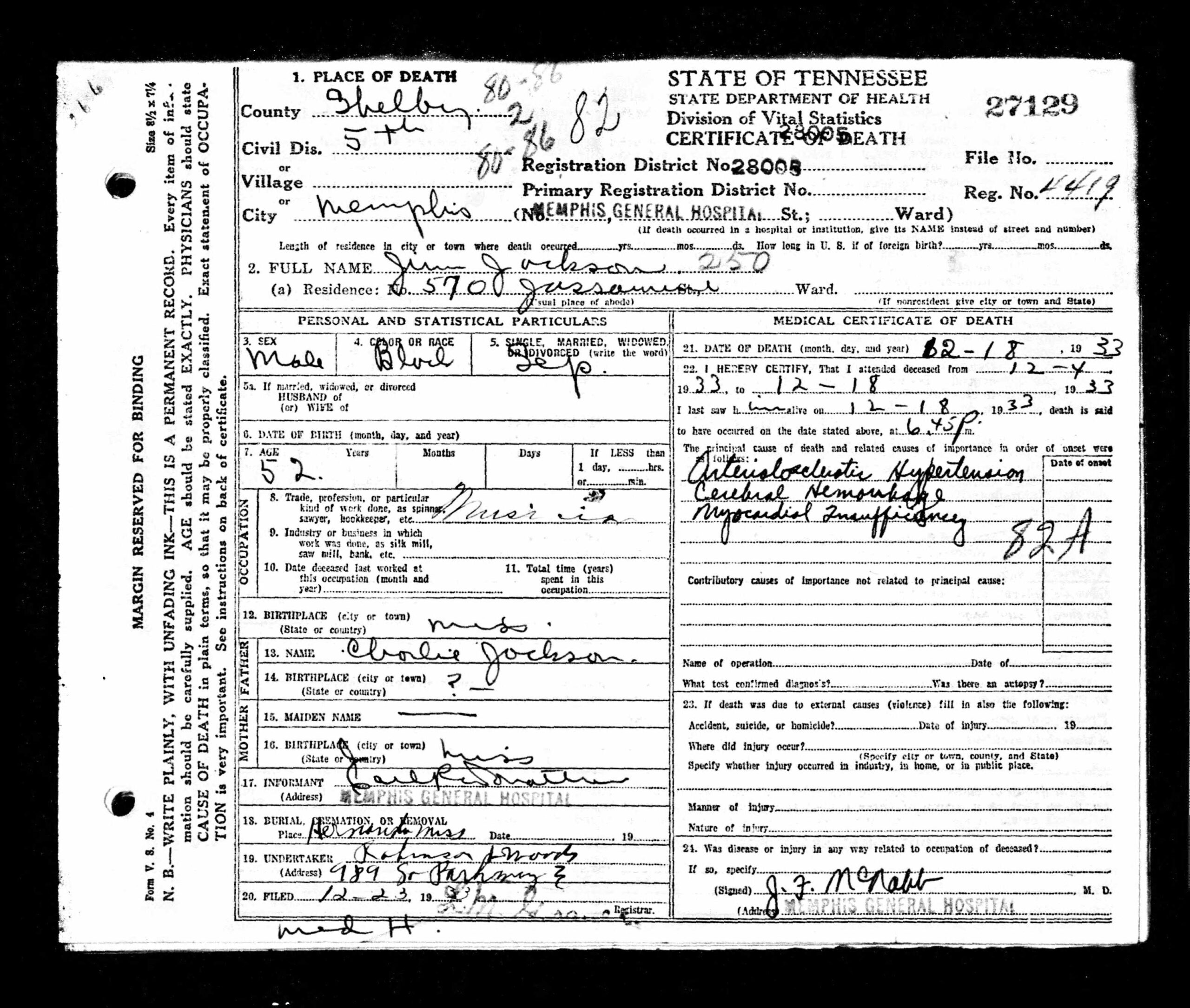

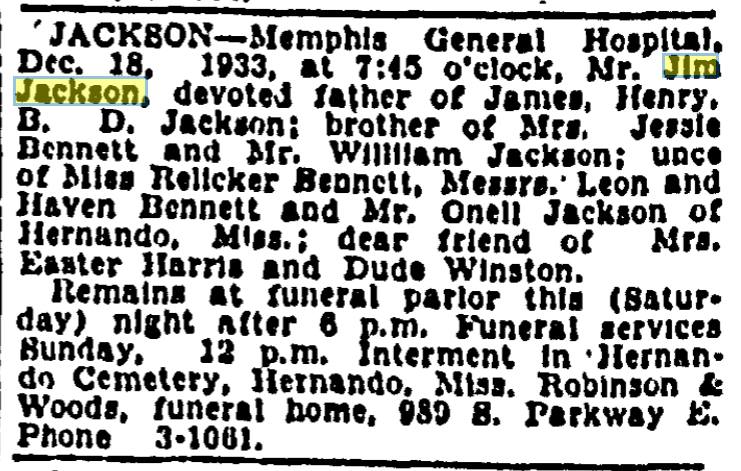

The Re-Generation grant from Monument Labs will support a pilot community-based participatory research, commemoration, and historic preservation project in Desoto County, Mississippi. The grave of 1920s and 30s blues artist Jim Jackson (who recorded the 1927 smash hit Kansas City Blues) remains unmarked in the segregated and abandoned African American section of Hernando Memorial Cemetery.

The pilot project will allow us the opportunity to research his life and career, track down his descendants and conduct oral histories, put together a diverse and inclusive group of musicians, community members, and other stakeholders to design the memorial, conduct a survey of the burial ground and document the names of internments with headstones, solicit information about the artist and the burial ground in the community, conduct oral histories with community members, organize and promote an inclusive dedication ceremony to unveil the memorial, and solicit funds for the perpetual maintenance of the cemetery.

We have already located a local, African American-owned landscaping business mortuary service, R&J Removal and Mortuary Service. The owner, Quincy Randal, is prepared to help us clean-up and maintain the cemetery in perpetuity.

The memorialization of Jim Jackson will also serve as the promotional vehicle for the launch of our Blues & the Commemorative Landscape Atlas and website, a publicly accessible digital archive and interactive map of Blues communities, which will heighten public awareness and raise historical consciousness. It also provides an opportunity for greater collaboration with descendant communities:

The Atlas will provide a survey to identify cultural phenomena unique to Blues communities in Desoto County, Mississippi and offer descendant communities an opportunity to achieve their economic development and historic preservation goals. The pilot project in Desoto County will serve as an example of how to conduct similar projects and eventually expand to all 82 counties in the state.

Potential Partners/Fiscal Sponsors

1. Rev. Leona Harris, director of the Ida B. Wells-Barnett Museum in Holly Springs, MS.

2. Chandra Williams, Executive Director at Crossroads Cultural Art Center in Clarksdale, MS

3. Mary Francis Hurt, director of the Mississippi John Hurt Foundation in Avalon, MS

4. Patricia Wilson Aden, president of the Blues Foundation of Memphis, TN

(Left) MZMF secretary T. DeWayne Moore & MZMF Treasurer Kechia Patton Brown, the great granddaughter of seminal Delta blues artist Charley Patton

(Center) MZMF President Annise Bradley, torchbearer for the Young Family Fife & Drum tradition and the granddaughter of Senatobian instrumentalist Abe "Keg" Young

(Right) MZMF Vice President Shannon Evans

A Biography of Jim Jackson

By T. DeWayne Moore

August 3, 2021

Jim Jackson was one of the seminal musicians who developed the unique and gentle, yet rhythmically solid, kind of blues in the adjoining hill country counties of DeSoto, Tate, and Marshall Counties. Ideal for dancing, with the singing having much in common with the old field hollers, it later became very popular in the medicine shows that toured the South. The reason for its popularity and its diffusion was not only the dominating influence of fellow Hernando-native Frank Stokes, but also the popularity and well-travelled career of Jim Jackson.

Some time around the beginning of this century Jackson moved a few miles north, to Memphis, to play in the gambling halls along Beale Street, at parties and Sunday suppers given by white folks. So did large numbers of African Americans from the north Mississippi hill country. Among the bluesmen who followed in his steps were Garfield Echols (Akers) and Joe Callicott from Nesbit in DeSoto County; and Frank Stokes and Robert Wilkins from Hernando.

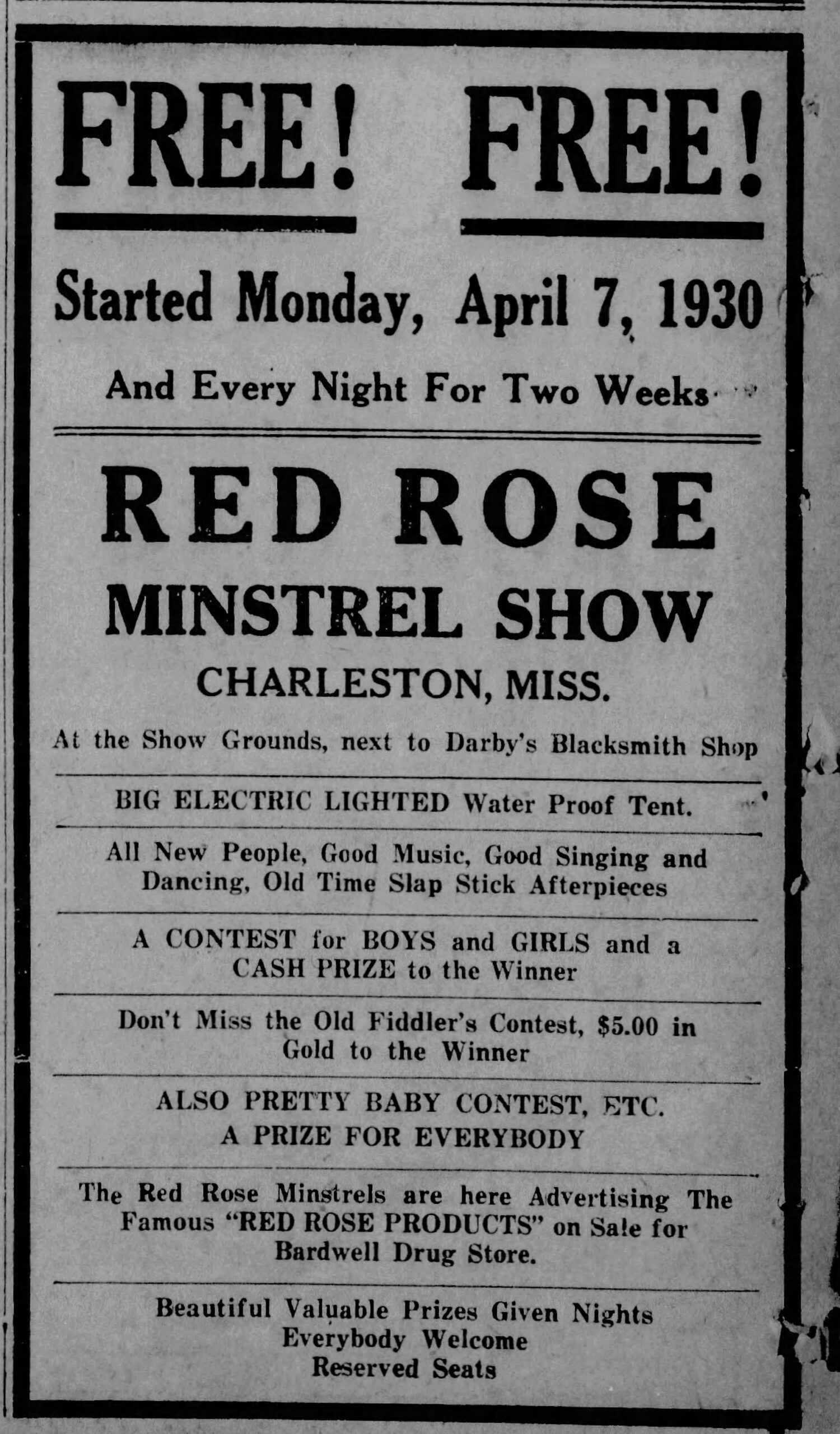

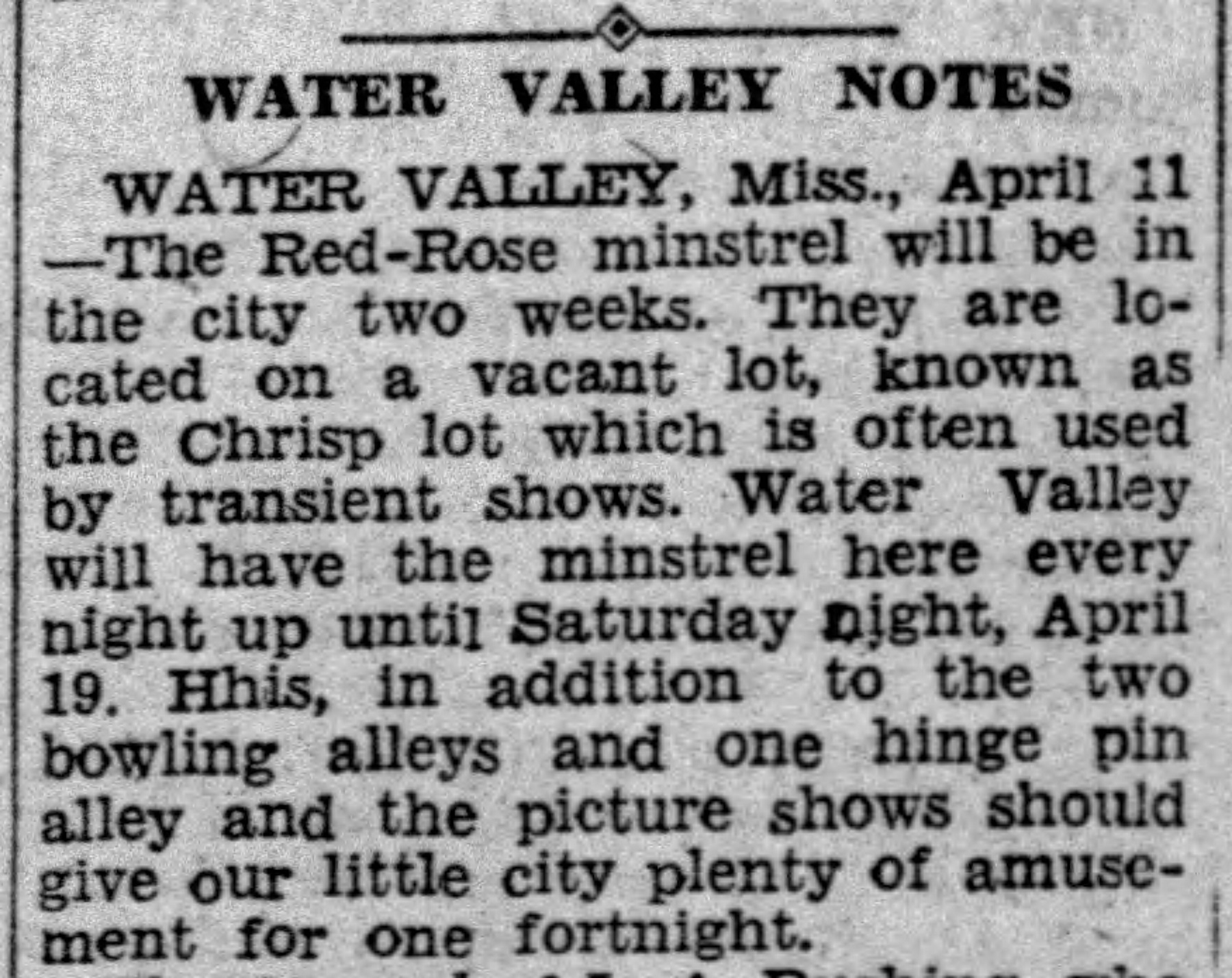

Jim Jackson traveled extensively with different medicine shows from about 1915 until the early 'thirties. He started with Silas Green's and Abbey Sutton's shows; then for a long time traveled with the Rabbit Foot Minstrels, one of the largest groups. Apart from singing, he danced and told jokes, helping to sell the medicine that was 'guaranteed' to do you good. He is also recalled as having toured with the Red Rose Minstrel Show, all over the south, in 1928; he was joined by Speckled Red, with whom, on one occasion, he recorded.

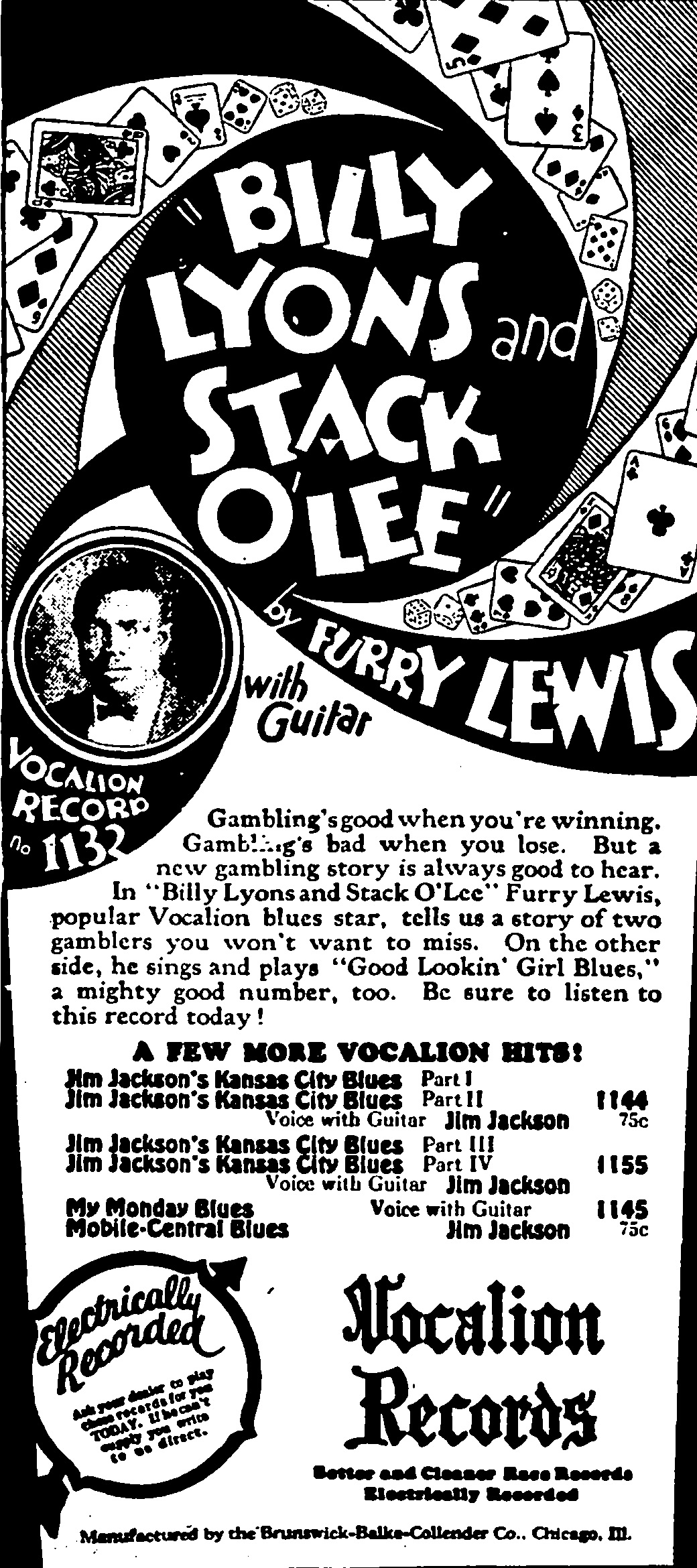

Jim Jackson entertained crowds and helped sell the Jack Rabbit Salve of Dr. Willie Lewis, whose medicine show was large enough to support a jug band, in which Jackson became a mentor of sorts for several future Memphis recording artists. Jackson's jug band included Will Shade, who went on record with the Memphis Jug Band, and Walter "Furry" Lewis, who later travelled with him to Chicago and recorded in the famous first session that produced Kansas City Blues.

Jackson spent many of his active years working in medicine shows, which provided employment for innumerable blues singers and songsters. Gus Cannon, for example, would organize his popular Jug Stompers after playing in Jackson's jug band for Dr. Willie Lewis's show. He previously had travelled every year in one medicine show or another with his guitar-playing partner Hosea Woods. Cannon started at home on South Parkway in Memphis with Dr. Stokey's show, and he met Chappie Dennison, who played a piece of plumbing pipe, on the show of Dr. W. B. Milton. After he got the idea to play a jug, he played on the shows of Dr. Benson and Dr. Hangerson, and Cannon explained, "I worked with a man out of Louisville. I worked through Mississippi. I worked through Virginia. I worked through Alabama, [and] I worked through Mobile, Gulfport, Bay St. Louis—far as I been down, playin' my banjo on them doctor shows."

Medicine shows set up their stages on vacant Iots in southern townships . A young "doctor" in Stetson hat and goatee beard introduced a team of performers; a few "hoofer" dancers, perhaps, or a jug band, or just a young man "cutting the pigeon wing" to the stop time guitar of his accompanist. With no scruples about selling the medicine, the doctor produced a bottle of miracle tonic and one troupe member, after taking a swig, feels impressed to approach the nearest woman as proof of its efficacy. The crowd responds raucously and bottles start selling.

In the South, African Americans had very limited options for medical treatment, and the clinics that offered free treatment were a mere handful. Thus, the tonics sold in medicine shows were at least some kind of relief. While the "doctors" mostly lacked qualifications and sold worthless medicaments, the preparations did relatively little harm and sometimes did good. To drum up interest and soften crowd resistance, medicine show doctors travelled with a small company and set up for only a brief stand in each community.

Jim Jackson worked in the Red Rose Minstrels with the pianist Speckled Red. Setting up in towns across the states of Mississippi, Arkansas and Alabama, it was a medicine show, according to Speckled Red, where:

"the man sold all kinds of medicine and stuff. One medicine good for a thousand things — and wasn't good for nothin'. A whole lot of pills, everything. He had a big show where there was a whole lot of women and I was playing pianner. Sometimes I was on she stage, trying to dance, and I could talk, crack a whole lot of jokes — me and Jim [Jackson]."

Jackson sang old minstrel show songs such as In the Jailhouse Now or Travellin' Man, which offered stories about the lived experiences of African Americans in the Jim Crow South, and he boosted the morale of crowds with stories about heroes who outwitted white folks. Uninhibited by the perpetuation of racial stereotypes, Jackson raised a warm response with lyrics that highlighted the economic inequalities of racial segregation. In the last two verses of a song he recorded as Goin' Around the Mountain in 1928, he explained:

Furry Lewis: "used to hear about him down in Greenville. He used to travel with the medicine shows, you know. I played with Jim Jackson. You know, he could pick a guitar just like I did. Sometimes just us two was playing together. Jim Jackson's been dead about thirty years ago. I couldn't tell you if he was two or three years older or younger than I. We was about the same age."

Gus Cannon: "I was at the same recording session as Jim Jackson when he cut Kansas City Blues. We used to play together in Memphis in the streets and, in medicine shows. Sometimes he would play with Frank Stokes too. The people who recorded Jim didn't allow me to play with him on the records. He was from Hernando."

Photo: Jim Jackson and filmmaker King Vidor on the set of Hallelujah in 1928.

King Vidor talks about his decision to shoot the film about the blues in Memphis, Tennessee in The Los Angeles (CA) Times, November 11, 1928.

Blues & the Commemorative Landscape Project

[Annise Bradley, DeWayne Moore, Shannon Evans, and Kechia Patton Brown]

August 3, 2021

Blues & the Commemorative Landscape Project

[Annise Bradley, DeWayne Moore, Shannon Evans, and Kechia Patton Brown]

August 3, 2021